A guide to investing your lump sum to generate passive income.

Seeing your company get acquired can feel bittersweet.

It’s a culmination of years of hard work towards what used to seem like a pipe dream. Now, here you are with a lump sum of cash, thinking about your next move.

Considering what’s next might surface some stress — since when was receiving a potentially life-changing amount of cash supposed to be anxiety inducing? But your feelings are valid. You want to handle your newfound wealth responsibly and not screw this opportunity up.

On top of your bank account looking drastically different, so too may your lifestyle. There’s a good chance you’ve suddenly transitioned from having a full-time job to not working at all. With that comes a cease in receiving direct deposits every other Friday.

Though navigating so many changes at once is uncomfortable, the good news is these sudden shifts are moving you in the right direction.

What you need to focus on now is devising a solid investment plan for your lump sum, which will allow you to continue living as if you’re still receiving a paycheck. Completing this step is key to smoothly navigating your transition. The acquisition transition, if you will.

This post outlines everything you need to know about turning your lump sum into passive income that helps you achieve your dream life.

Understanding acquisition payment methods

For starters, you’ll want to understand the type of acquisition payment method you’re dealing with, of which there are two:

- All cash: This usually results in a large lump sum.

- Combination of cash and stock acquisition: This entails receiving a lump sum, along with some equity in the company that acquired your company.

The key difference between these two types of payments is that with an all-cash acquisition, the lump sum you receive is the end of the process. With the cash-stock combination, the lump sum may just be the beginning of it.

Disclaimer: Before we dive into specifics below, I want to clearly state that this post is based on real people we’ve worked with who were in your same shoes at one point. I’ll be transparent and specific about investments we use with these individuals, but in no way should this post be misconstrued as investment advice. The post is simply intended to illustrate a process we use to help professionals navigate turning their lump sum of post-acquisition cash into a well-defined income investment plan that supports their goals and provides them with the income they need.

Planning your lump sum income investment

There are several phases to handling your lump sum, which I’ll outline below.

Throughout this post, I’ll use $3 million as an example lump sum, but the post’s overall sentiment should apply to anyone who has a large, post-acquisition lump sum on their hands, regardless of the exact dollar amount.

Let’s dive into the process.

1. Becoming tax aware

When our team works with someone who’s received a $3 million lump sum from an acquisition, the first step we take is becoming tax aware. Because your lump sum is subject to taxes, your $3 million payment isn’t exactly what you’ll walk home with — not even close. Sure, you’ll have less than the total lump sum to invest after taxes regardless, but you can still maximize how much money you take home by properly handling your taxes.

To get your tax ducks in a row, gather all the documents related to your acquisition. These documents outline the equity that’s been converted into cash. With your documents, we can determine the tax treatment, project your expected tax bill, and determine whether making estimated tax payments is necessary.

Another thing to look out for is whether you’re dealing with qualified small business stock (QSBS) because it requires special tax treatment. Failure to properly treat shares that may have been sold as QSBS could cost you hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of dollars in taxes that you don’t actually owe. This is just one of the many reasons you’ll want to work with an experienced professional who’s dealt with acquisitions and QSBS in particular.

Being on top of your taxes is especially important in acquisitions because there’s a considerable amount of money at stake and you want to keep as much of it as possible. While taxes rarely tell us what we should do, they often inform how we execute our investment plan.

2. Keeping cash

As we build an income investment plan, we usually start by figuring out how much cash to keep on hand. How we keep that cash — free checking account, high-yield savings account, CD, money market fund, treasury note, etc — is just as important, especially now that there’s been a dramatic reversal in monetary policy in the US and an increase in interest rates. These conditions have caused an inverted yield curve — the first one in a long time. What that means is short-term securities, which are issued with early maturity of a year or less, are actually paying higher rates than long-term securities like a 10-year treasury. That said, you’re currently not being rewarded for taking on additional term risk by going further out on the yield curve, but that also means you’re being rewarded for keeping cash — a longtime first. How and where you kept your cash didn’t matter a few years ago because every option paid 1% or less. But with today’s inverted yield curve and high interest rates, where you keep your cash matters. It’s the difference between earning less than 1% on your cash versus earning 5% or more on it.

A discussion about cash isn’t complete without considering your goals. Are there any specific things you’re hoping to fund with this lump sum? Goals can vary from very specific ones (like buying a second house by the beach next year) to vaguely general ones (like setting aside money for your kids’ college education). Your more specific goals are usually the ones you want to do in the next one to three years, whereas your less specific ones aren’t as pressing and won’t happen for at least another three years. Start identifying your goals because they may influence how much cash you keep on hand.

To determine the specific amount of cash you keep, start by estimating your tax bill and keep that amount in cash. Then, consider replacing your current salary with cash. If your salary is $300,000 and you’re getting a lump sum of $3 million, it’s not a bad idea to carve out $300,000 cash to have on hand. If you’re considering or planning to stop working, having an entire year’s worth of your usual pay on hand can ease any worries you have for your first paycheck-free year. Beyond that, look at your specific, one-to-three-year goals and assign prices to them. Consider keeping that amount in cash as well, or include it in the fixed income portion of your portfolio.

3. Assessing risk & return

Once you’ve identified the amount of taxes you might owe and the amount of cash you’ll keep on hand, you’ll know how much of your lump sum is actually available to invest long term (i.e. for more than three years). With every investment comes risk, but some avenues are more dicey than others. How should you invest your money and what’s the balance of risk and return you want to take with your portfolio?

Before answering those questions, understand the direct relationship between risk and return. The more returns you want to potentially receive, the more risk you must take. The only way to decrease risk is to accept lower returns.

As we build out clients’ investment portfolios, we discuss a few things related to risk and return:

- How they want their portfolio to perform

- What they actually need their portfolio to do

- How much risk they’re comfortable taking

- What return they need for their portfolio to support their living expenses and goals for the rest of their life

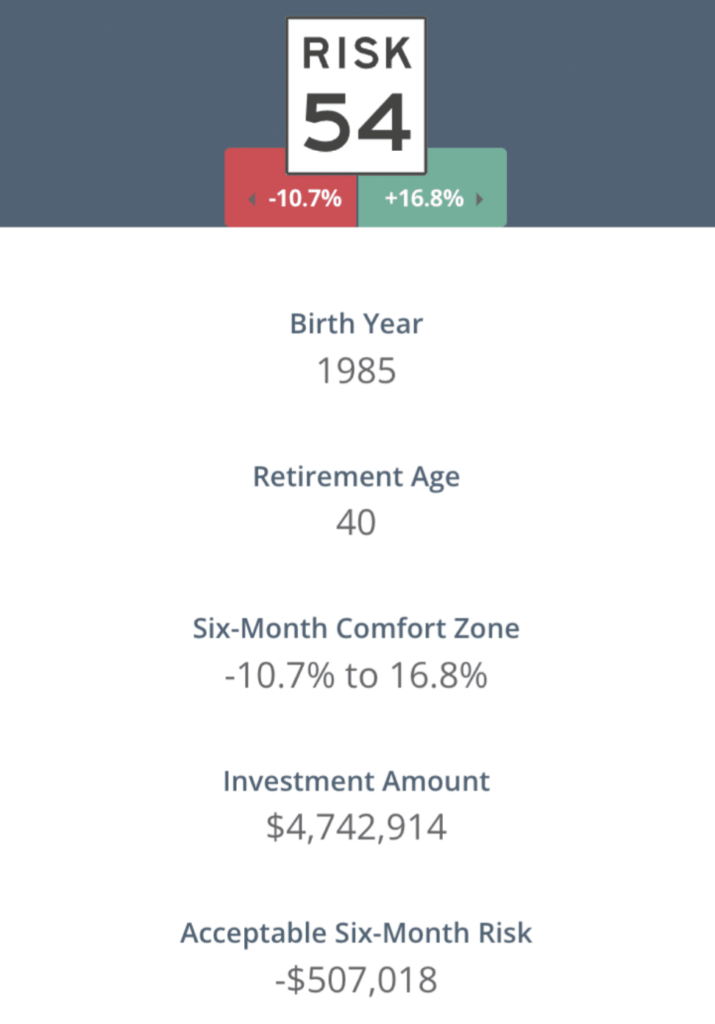

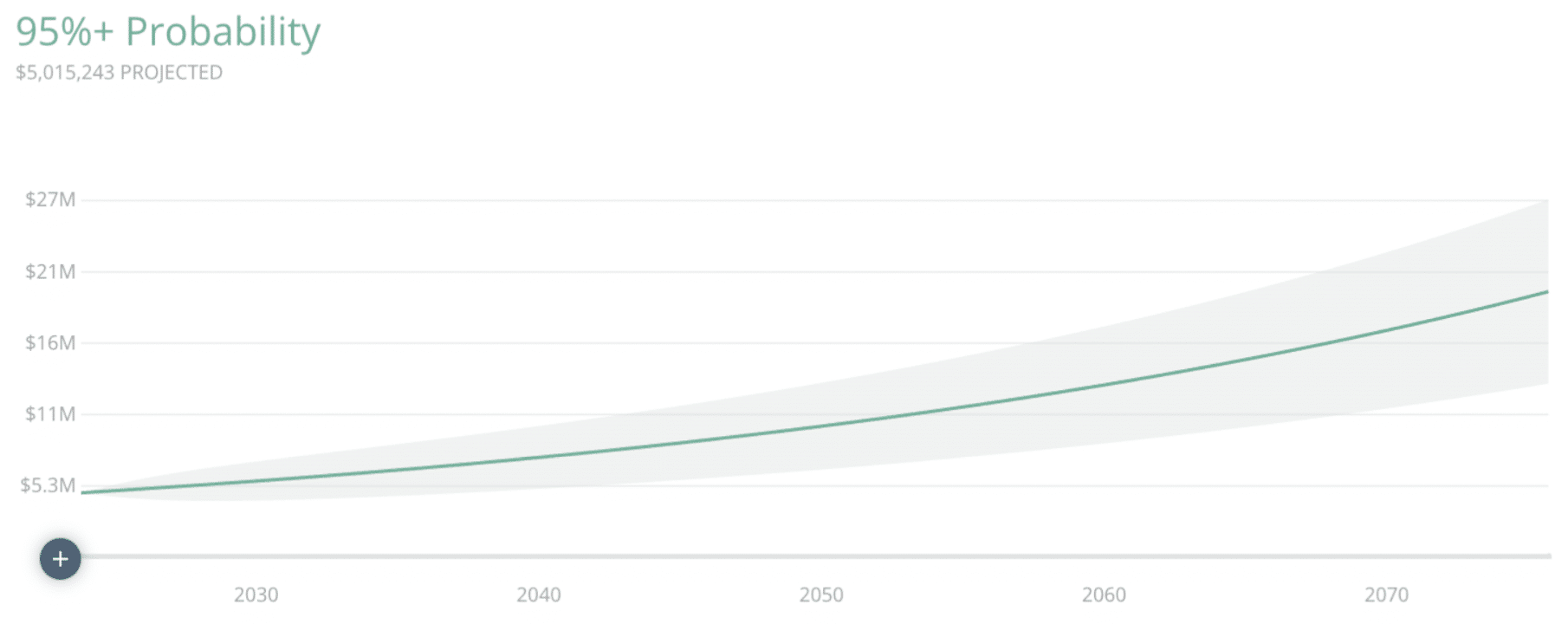

To strike the right balance of risk and return in clients’ portfolios, we use a tool called The Risk Number, which quantifies how an individual wants their portfolio to perform.

The Risk Number is an objective, quantitative measurement of an investor’s true risk tolerance and the risk in a portfolio.

The Risk Number is simply a questionnaire we answer with each client. At the end, it assigns a risk number, which it likens to a speed limit: You can drive slow and be safe, or drive fast knowing you’re taking on additional risk. Your risk number gives you a way to quantify your comfort with the relationship between risk and return over a six-month period. WIth this tool, you can gauge what you consider an acceptable six-month risk, meaning the lowest you’d be willing to see your portfolio fall over the next half year.

So once we use The Risk Number to define how clients want their portfolio to perform, we set the risk number. Next, we determine whether the client’s want (i.e. their risk number) fits with what they actually need. We do so by examining the probability of success for their portfolio invested according to the risk number you want. Based on that, we can make adjustments to get their wants and needs to match. From there, we develop a proposed mix of fixed income and stocks for the investment portfolio.

Your retirement map determines your needs as you build your fixed income portfolio.

4. Understanding fixed income

A move I’ve observed many clients make is immediately focusing on fixed income. It’s usually because they left their job after the acquisition and feel pressure to replace their paycheck and cover their living expenses.

This thought process isn’t outright wrong but if you accompany it with thoughts along the lines of, “I’m going to invest my $3 million for income. It’ll yield 5%, which will give me $150,000 of income,” this mindset can lead you to make short-sighted investment decisions that can hurt you in the long run. Metrics like The Risk Number and your retirement amount help shift you into a more long-term mindset with your planning.

Avoid fixed-income bond index funds and ETFs. Most of them are market-weighted, similarly to stock index funds and ETFs. That means they’re typically long-term and hold bonds from whatever government or company borrows the most money. I’m not convinced owning debt from the largest borrowers is a good way to build out the fixed income portion of your portfolio.

Here’s a better approach (in my opinion).

We use Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) mutual funds and ETFs, both on the fixed income and the stock side. One of the greatest advantages of DFA bond funds and ETFs is they take a variable maturity and variable credit approach, which I’ll explain in a moment. Earlier we talked about the inverted yield curve, which is often referred to as a single curve, but it’s not. There are multiple yield curves, including one for government debt and another for corporate debt, etc. The DFA bond funds and ETFs use information from these multiple yield curves and vary the target maturity and target credit of the fund based on the information in those yield curves. This variability has been especially important over the last three years, as the average maturity of the total bond market index fund hasn’t changed at all. That’s because the fund just simply matches an index regardless of market conditions. Total bond index funds have taken a beating over the last few years, performing similarly to an entire stock market index fund. Conversely, DFA bond funds and ETFs’ variable maturity approach have all been reacting to the inverted yield curve. That means as bonds within those funds mature, they’re not reinvested to match an index; they’re instead based on the yield curve data, which means the maturity of those funds has been shortening. The disparity between the total bond market index fund and DFA bond funds and ETFs is especially apparent when you examine the funds’ annual returns. Investors who use index funds tend to use the total bond index fund, which limits them to US government and corporate debt, however the US is just one part of the global fixed income market. Investors should instead build a global bond portfolio to get higher returns with less volatility, which DFA makes easy

Now, how do you go about actually building your fixed income portfolio? It’ll be informed by your risk number and your needs, as indicated by your retirement map. Beyond that, we can take a stair-step approach, similar to what we did in the cash section above. Start with the one, two, and three year timeframe. Determine your living expense needs for years two and three — not for year one because that’s already covered by cash. Then, use funds like the DFA One Year Fixed Income (DFIHX) fund as well as the DFA Two Year Global (DFGFX) fund to build out your living expense needs for years two and three. Beyond three years, you may look at the DFA Five Year Global (DFGBX) fund or the DFA Investment Grade (DFAPX) fund.

Many of my clients ask whether municipal bonds should be at play in the fixed income portion of your portfolio. The municipal bond decision should be based on an analysis of your tax situation as well as the yield and maturity in those municipal bond funds. It’s important to ensure you’re being rewarded with after-tax returns that are higher in municipal bond funds than they are in a regular bond fund. It also needs to be a clear case because opting for municipal bonds funds means giving up the greater diversification that comes with taking a global approach, versus trying to eke out tax savings with a municipal bond fund. Your tax situation is also important here because you may go from a high tax bracket prior to the acquisition to a low tax bracket after the acquisition if you stop working. In that case, you should question if you really need the potential tax savings. If you do, it just makes the math harder to work in your favor. Odds are you won’t be rewarded with a higher after-tax return from the savings that you get with municipal bonds.

5. Harnessing the power of stocks

The stock portion of your portfolio is the main driver of long-term growth and appreciation in value. Over your lifetime, stocks will be the most significant source of cash to replace your income. They pack much more of a punch than anything you can do with fixed income and yields, so you’ll want to set yourself up for success here.

To get the most out of the stock portion of your portfolio, you should:

- Diversify: Investing in a diverse stock portfolio increases your odds of obtaining a historic expected return. Limiting yourself to a single stock or a handful of them exposes you to the unpredictability around how they might perform down the road. Instead, invest in tens of thousands of stocks from all over the world so you can take a global approach, just like with the fixed income portion of your portfolio. In return for that diversification, you’ll get an expected return you can somewhat reasonably count on. There are certainly exceptional years that see huge deviations from average expected returns, but over your lifetime, things will even out and you’ll get somewhat close to the total expected return.

- Pay low costs: Invest and build it out in a low-cost manner. Costs, fees, and expenses matter — though not as much as diversification. Still, pay attention to them.

- Leave it alone: Build it in such a way that you can leave the stock portion of your portfolio alone and let it do its thing. Being hands off is the best thing you can do for your stock portfolio — and frankly, for your entire portfolio. Don’t make investment choices based on market conditions or predictions.

There are also a couple things you’ll want to avoid when building out the stock portion of your portfolio:

- Individual stocks: You may be tempted to start buying stocks from companies you’re familiar with and that you think will be winners. The problem is this risky approach lacks the benefits of diversification and may even require additional costs to build out your portfolio. Buying an individual stock is an easy choice, but doing so introduces a second, more difficult choice: deciding when to sell.

- Cryptocurrency: Similar to individual stocks — but with exacerbated risks — is crypto.

If you find the excitement of individual stocks or crypto appealing, consider investing in individual pieces of real estate instead. You’re more likely to get an above average return investing in real estate than you are investing in individual stocks or crypto, while still getting somewhat of a thrill. Overall, the benefits are greater and the returns are more certain.

I know I just said to avoid using your lump sum to buy individual stocks, but there’s a smarter way to do it. You can incorporate individual stocks in your investment portfolio through a separately managed account (SMA), which is a form of direct indexing involving portfolios greater than $2 million. Instead of buying a mutual fund or ETF, you can simply recreate the mutual fund and ETF with an SMA. Instead of having ten or 20 individual stocks, the account will have more like 1,500 of them and they’ll closely replicate the entire US stock market. With this strategy, you can then have management decisions made down at the individual security level. This comes handy around topics like tax-loss harvesting or donating appreciated securities to charities, the latter of which would help you both get an income tax deduction for charitable giving and avoid the long-term capital gains you’d have paid if you sold the position. SMAs also allow you to customize the approach the account takes. This includes making adjustments based on any preference for or aversions to particular companies or sectors.

Say for example your acquisition is both cash and stock and you anticipate ending up with a lot of stock from a publicly traded company. We can exclude that company’s stock from your SMA to prevent making the concentration risk of the stock portion of your acquisition any worse.

6. Creating cash

Something professionals tend to struggle with the most is figuring out exactly how to create cash from their investment portfolio.

They ask. “How can I take a lump sum and turn it into a reliable income source for the rest of my life?”

Though it’s tempting to make passive income investing very straightforward, it’s not as effective. By straightforward, I mean investing in a fund or purchasing a bond, and pocketing the dividends or interest you receive as income. I’d argue this approach is shortsighted. If you follow it to an extreme, you may experience conflict between what you want from your portfolio (straightforwardness) and what you actually need from your portfolio (something that will last a lifetime and sustain your needs).

A more strategic way to create cash is rebalancing your portfolio. Start with the amount of cash you should have on hand right now and keep at least enough to cover your living expenses for the next year. Then, take the remainder of your lump sum and put it into a diversified investment portfolio, involving a mix of fixed income and stocks. Over the next year, that portfolio will move around. Some portions will perform better than expected, while others perform worse. Though it’s impossible to predict each portion’s performance, one thing we know for sure is that the portfolio mix will change over the year that you have it.

Simply rebalancing your portfolio is the easiest way you can create cash to replace your income and cover your living expenses. So, at the end of the year, you’ll see the targeted allocation you started with and compare it to the current allocation 12 months later. Determine the funds in your portfolio that are now overweight (that means the percentage allocated to those funds now exceeds the target we’d set for that fund initially). Then, sell those overweight positions to get them back to their targeted allocation. Keep the proceeds from that sale as cash to replace your income and cover your living expenses for the next year.

For four out of every five years, you’re probably going to use stock gains to replenish cash. But bad stock years happen — how can you get through those? That’s why we have the fixed income portfolio of one-to-three-year bond funds. three-to-five-year bond funds, and five-plus-year bond funds. Having a diversified portfolio protects you from bad stock years. When you encounter one, start with those one-to-three-year funds and use them to provide your cash so that you’re not selling stocks in a down year. And if the down year continues, go from the one-to-three-year funds to the three-to-five-year funds, and usually by the time you get to five-plus-year funds, the stock portion of your portfolio will have started to recover. At that point, you can return to your normal approach of using the gains in your stock portfolio to replenish your cash.

The last few years have been a perfect example of this approach. Here’s how we would have handled our hypothetical income investment portfolio each year, starting in 2020:

2020: We kicked off the year with the Covid crash in March, but by the end of the year, the stock market had recovered. The downturn was temporary and all we would’ve had to do that year would have been to wait for the market to recover within that same year. We would have likely used some of the bond funds in 2020 to temporarily replace income, but by the end of the year, we would’ve used the stock portion of our portfolio to create cash

2021: All of 2021 was a boom year. The stock market was way up and we would’ve been exclusively creating cash from the stock portion of our portfolio.

2022: But then in 2022, there was a change in monetary policy, the dramatic reversal in interest rates, and a down year in both the stock and bond markets. Tapping into the short-term portion of the fixed income part of your portfolio would’ve been crucial to avoid selling your other funds.

2023: Fast forward to 2023, many portions of the stock market are back to the level they were last at in 2021. This year, we can return to using your stock portfolio to create cash.

Starting in post-acquisition year two, you’ll want to get into a good annual flow and process. Do an annual plan update and tax projection, which is essentially an abbreviated version of the initial work we did in the beginning of this blog post. Based on your tax projection, your portfolio performance, and the market’s performance, we can start to determine how to replenish cash looking into next year. Once a year, you’ll want to look at replenishing the cash you need for the next 12 months and do so in a way that rebalances your portfolio.

Start planning your dream life

We covered a lot of ground. I hope you feel more prepared for your acquisition transition after reading this.

You (likely) only get one big acquisition in your life, so don’t take this opportunity lightly. If done right, your investment portfolio can make your dream life a reality.

Our team at KB Financial Advisors has helped many professionals in your same shoes, so we know a thing or two about getting you on the other side of your acquisition. Book a call today to talk to myself or another expert on our team about how to fuel your dream life using your post-acquisition lump sum.